Tõnu Seilenthal on cooperation with the Finno-Ugric peoples of Russia

Fenno-Ugria Project Manager Janno Zõbin spoke to Tõnu Seilenthal after the Finnish-Russian Society seminar in Kuhmo on 14 June, about what was said at the seminar and cooperation with Finno-Ugric Russians in general. The interview is published in Estonian on Sirp.

– –

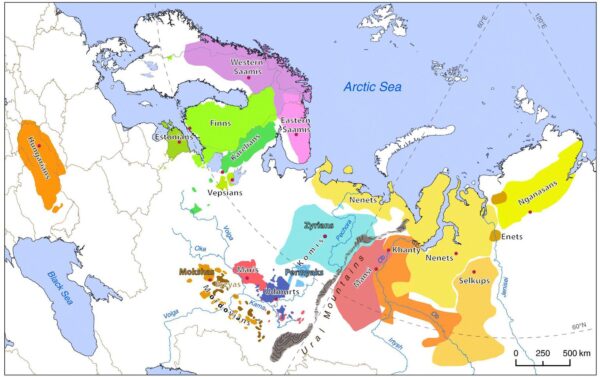

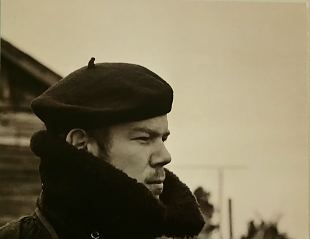

Linguist Tõnu Seilenthal is one of the longest-standing leaders of the Finno-Ugric movement. For almost six decades, he has maintained and developed cultural ties with our cousins Finns, Hungarians, Votes, Khanty and others. At the end of the sixties, Seilenthal acted as a consultant for Lennart Meri’s film “The Waterfowl People”. He has been visiting Finno-Ugric peoples in Russia since 1966. His work with them has also brought him into contact with the Finnish-Russian Society in Finland. The situation and activities of the Society have now changed due to the Russian-Ukrainian war. We talked about cooperation between Finno-Ugric peoples in the current circumstances.

Tõnu Seilenthal, could you please tell us about the seminar in Kuhmo, Finland, on “What’s next? State of Finnish-Ugric cooperation”. Why did you attend?

I was chosen to participate in the seminar by Fenno-Ugria, the Estonian representative organisation of Finno-Ugric peoples. The Finnish-Russian Society, which organised the seminar, is considered by the radical Finno-Ugric people to be too pro-Russian, but already in the early days of the war in Ukraine they clearly condemned the war. I felt that we should continue to engage with them.

At the seminar, Pekka Huttu-Hiltunen, Director of the Runosong Academy, introduced the tradition of Finno-Ugric Capitals of Culture and the activities of Kuhmo, this year’s Capital of Culture. Olga Gokkoeva, Honorary Chairwoman of the Karelian Kielen Kodi Association, spoke about the situation of the Karelian language in Finland, and especially in Karelia. I spoke about the eight World Congresses of Finno-Ugric Peoples that have taken place so far, and how these congresses have manifested the contradictions between the peoples and the authorities. In his presentation, Riku Savolainen discussed the extent to which cooperation with Finno-Ugric people living in Russia is possible at all at the moment. The question and answer session was also devoted to reflections on both the possibility and impossibility of cross-border cooperation.

To what extent is cultural cooperation between Finland and Russia taking place at all these days? How have the Society’s activities changed during the war?

Since the Finnish-Russian Society can no longer invite representatives of Finno-Ugric peoples living in Russia to Finland, their funding has been reduced. Finnish-Russian cooperation, which had lasted for decades, has essentially ceased. The Russian Federation recognised the Society as an extremist organisation in spring 2022, so their attitude is clear. (The Estonian Fenno-Ugria has not yet received such ‘recognition’.) The Russian authorities also closed down the Russian Scientific and Cultural Centre in Helsinki, whose last director was the Udmurt Alexei Zagrebin. Finland, for its part, closed down Suomi-talo, which was located in the immediate vicinity of Nevsky Prospect in St Petersburg.

What are the representatives of the Society’s partners in Russia saying about the war?

In the case of my parents and even older ones (Tõnu Seilenthal turned 76 on 28 June – J. Z.), I can even understand their chauvinism, although it is difficult to understand. I’ve seen it before, for example, in the late 1990s in Leigo in southern Estonia, when at a meeting of the Consultative Committee of Finno-Ugric Peoples a little more vodka was drunk and then some Khanty or representative of another nation wanted to come up to me and say that you Estonians have betrayed us. That my grandfather fought for your freedom and you don’t appreciate it at all. You want your own country, but we can come and conquer you at any moment. It is even more difficult to understand the fourty- and fifty-year-old pro-Kremlin Finno-Ugric people. How to communicate with them, I do not know.

I also remember when there was a war in Georgia in 2008 and I met some Finno-Ugric people at a seminar in preparation for the International Finno-Ugric Congress in Piliscsaba, Hungary. I met a person there who explained to me, blue-eyed, that the Georgians wanted to start destroying Russia. The only thing I could say was, you have had enough of expressing your thoughts, so let us drink this vodka and go to bed.

Some Finno-Ugric people who have studied in Estonia with the support of the state have also expressed politically interesting alternative views. Why have some of them become Kremlin supporters?

Yes, it is hard to understand why, for example, a student at the University of Tartu is organising the recruitment of boys into the army in Russia, compiling a booklet of conscript songs and organising ceremonial military parades for conscripts. For me, it gives me a feeling of overwhelming depression. This is an activist who, because he was a leader of the legendary Finnish-Ugric Youth Association (MAFUN), was beaten so badly that he was dying in hospital. The rector of Izhevsk Medical University at the time arranged for him to have a quick operation in Russia, and shortly afterwards he was rescued and allowed to continue his studies in Estonia.

Is MAFUN still active today?

As far as I know, it has not been officially active for eight years. In 2015 there was a MAFUN Congress in Tartu and in 2017 it was supposed to take place in Izhevsk. The congress was postponed, but it has not taken place until today. The reason seems to be the Kremlin’s idea that there is a phenomenon called Finno-Ugric separatism. At the same time, cultural festivals of Finno-Ugric peoples still take place in Russia, and quite often. Of course, Finno-Ugric people living in Estonia do not go there now and the Finno-Ugric people do not come to us.

How easy is it for Finno-Ugric citizens of the Russian Federation to live and work in Estonia?

You never know who and for what reason is put into a difficult situation in Russia. In 2012, they introduced a foreign agents law, which means that as soon as your NGO receives money from abroad, you have to declare yourself a foreign agent and you get a bad mark. As a result, many NGOs are afraid to accept Estonian third sector money. They are also afraid to communicate with their relatives in Russia, for example, because of political disagreements with their parents.

How much contact do you have with Finno-Ugric people living in Russia?

I don’t know if it’s good for them if I call. I would rather not. I think they might be listened to, it’s easy to do that nowadays. In the old days, with the KGB, there was a question of where to get so much tape. Now there is no problem. With those who are not at the mercy of propaganda, I only exchange birthday greetings.

What is the future for Finno-Ugric organisations in Russia?

It is difficult to predict. The question is in what form and how they can continue after the war. What is going to happen is unclear at the moment – whether there will be settlements of scores between private armies, whether there will be a dozen smaller states, etc. The question is what will happen.

How realistic do you think this is? For example, in the case of the Erzyas, I think the issue was raised?

Yes, an Erzya activist and current Ukrainian officer, Syreś Boĺaeń, presented the map of Erzjan Mastor or Erzyaland in Otepää last October. Erzyaland is there three times bigger than the current Republic of Mordovia (nearly 60 per cent of the Russian Federation’s Erzya and Moksha live there). (The historical area of settlement of the Erzya on the territory of the Russian Federation includes the Republic of Mordovia, the Republic of Tatarstan, the Republic of Bashkiria, the Republic of Chuvashia and their neighbouring regions – Sirp.) He would then have to take territory from the Tatars and others. He wants to create a state of Erzya with an autonomous republic of Moksha and Tatars inside.

In any case, the Russian Federation authorities noticed.

Yes, it was highlighted at a meeting on ethnic relations in Russia on 19 May this year, chaired online by Vladimir Putin. Almost all the experts on ethnic relations were present, including the academic and ethnologist Valery Tishkov (the former Minister for Nationalities of the Russian Federation, who was expelled from the Estonian border in 2014 because of a travel ban, as it was suspected that he had not come to Estonia to make a scientific presentation, but as part of a hostile information operation – Sirp). The President of the Association of Finno-Ugric Peoples of Russia (AFUN), Pyotr Tultayev of Moscow, who is a senator of the Federation Council of the Russian Federation, also spoke. He reiterated his previously stated position that, in the current situation, he does not consider it necessary to continue the tradition of the World Congresses of Finno-Ugric Peoples. The reason given was that Estonians, Finns and Hungarians are trying to boss the Finno-Ugric peoples like their elder brother. That they look down on their own kin.

What has changed in the language and culture of Finno-Ugric people of Russia over the past five years?

The first big change took place in 2018, when the study of the mother tongue was made voluntary in the titular republics of Russia. This means that the mother tongue is taught only to those who wish to learn it. However, the number of those who wish to do so among Finno-Ugric people of Russia is quite small. This has a clear negative impact on mother tongue proficiency.

The stabile situation in Russia was disrupted by the corona virus, so the borders were closed, but it was also a good reason why some activists of the Finno-Ugric movement were not allowed to leave the country. At the border, it turned out on more than one occasion that the activist’s vaccination certificate was incorrect and not valid. There was no room for argument.

How is the war in Ukraine affecting Finno-Ugric identity?

My acquaintances all have two identities. The other one – in addition to the Mari or the Komi – is not Russian (ethnic), but Russian citizen (civic). In almost sixty years in Russia, I have not noticed any anti-Russianism among Finno-Ugric people.

What narrative does the Kremlin create about Finno-Ugric peoples in wartime? How does it want to portray them?

It seems to me that this narrative is not very important to the Kremlin, because there are now only about a million speakers of Finno-Ugric languages, while Russia has a population of 143 million. The trend towards the disappearance of the Finno-Ugric languages is clear to see, and Moscow does not need to do much about it. These small nations are hardly likely to cause any particular problems for the army of Russian Federation officials. They have much more to do with Muslims.

When could cultural cooperation between Finland, Estonia and the Russian Federation start again?

Maybe the first morning after the war. And let’s start with ordinary people.