Livonians

Currently there are only a few scores of speakers of the Livonian language, and nobody speaks it as a mother tongue.

Names

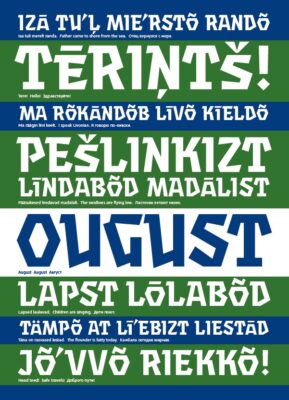

Livonians refer to themselves as rāndalizt (coastal people) and their language as rāndakēl (coastal language).

Territory

Livonians are among the smallest-numbered surviving Finno-Ugric peoples. Livonians live on the territory of the Republic of Latvia. Until recently they lived on the Livonian Coast of the northwestern coast of Courland (Kurzeme).

During the flourishing of Livonian culture betweeen the 10th and 13th centuries, Livonians also inhabited the upstream of the Daugava river, Toreida or today’s Sigulda-Turaida-Krimulda area near the Gauja river, Metsepole or the vicinity of today’s town of Limbaži, the lands around the Salaca river and the Idumea parish to the north of the Gauja river.

Historical (Old) Livonia does not refer to the lands inhabited by ethnic Livonians, but to the name that German crusaders assigned to the conquered land.

Population

Currently there are only a few scores of speakers of the Livonian language, and nobody speaks it as a mother tongue. Nevertheless, approximately 200 persons self-identify as Livonians, most of whom live in Riga, Ventspils and Kūolka. No fluent speakers of the Livonian language currently live on the Livonian Coast – the 12 coastal villages in Courland (Kurzeme) traditionally inhabited by Livonians.

According to scientists, there were approximately 15 000 – 28 000 Livonians in the 12th century. Over time, their numbers as well as territory declined, so that towards the middle of the 19th century only 22 persons remained in Livonian lands around the Salaca river and 2324 persons on the northern Couronian coast. The last Salaca Livonian died probably in 1868.

After World War I, there were approximately 1500 Livonians. Thanks to a dense population on the Livonian coast, they succeeded in preserving a Livonian-language environment. Still, Livonians began gradually resettling elsewhere, in most cases assimilating among ethnic Latvians. After World War II, 800 Livonians were living in the coastal villages. However, after these lands were classified as Soviet border area, majority of Livonians were forced to leave the coast in search for jobs.

Language

The Livonian language is among the oldest Baltic-Finnic languages. It is classified into the same group with Northern and Southern Estonian dialects and with Western dialects of the Finnish language. Based on this, scientists have concluded that Livonians are among the first Baltic-Finnic peoples near the Baltic Sea. In the reconstruction of the language tree, the Livonian language could be placed as one of the oldest languages between the dialects of Northern and Southern Estonian.

History

The first mention of Livonians dates back to 1113, to the chronicle of Nestor “Tale Of Past Times”. More extensive information about the ancient history and settlement of Livonians can be found from Henrik’s Livonian chronicle of the 13th century. Back then, Livonians inhabited primarily the lands around Daugava, Gauja and Salaca rivers. This is also where the city of Riga was built while the Livonians, according to chronicles, put up a struggle for their independence which lasted until 1206. Among the leaders of the Livonian people, Ako, Asko and Kaupo were mentioned.

First records about Couronian Livonians date from the 14th century. Based on archeological finds it has been supposed that the ethnic composition of North Couronian Livonians remained almost unchanged from times immemorial. Reports from the 17th century, however, point at close contacts with Saaremaa and its people.

During World War I, Livonian villages and the Livonian people suffered greatly. Many Livonians had to leave their homeland. Unfortunately the young Republic of Latvia did not prioritise the Livonian national question and did not establish conditions necessary for the preservation of this people.

Nonetheless, the years 1920-40 can be considered as a period of Livonian cultural flourishing. Livonian cultural and civic life was reinvigorated and the Livonian language was for the first time taught as an optional subject in schools. National choirs were established and opportunities were sought for training the youth. Contacts with Finno-Ugric kindred peoples were established and the Livonian language and culture was studied by several outstanding academics, including Lauri Kettunen from Finland and Oskar Loorits from Estonia.

In 1923, the Livonian central organisation Līvõd Īt (Liv Union) was founded, however efforts to establish a Livonian municipality did not succeed. On November 18 of the same year, the Livonian national flag – a green-white-blue tricolour – was consecrated in the Īrē (Māzirbe) church. During the same period, the Livonian national anthem was written by Kōrli Stalte, with the identical melody as Estonian and Finnish national anthems.

With the support of Estonia’s, Finland’s and Hungary’s Finno-Ugric movements as well as the Republic of Latvia, the Livonian community house was opened in 1939 – this can be considered as the only tangible result of the Finno-Ugric kindred peoples’ movement (at least from that period).

The establishment of the Soviet rule in Latvia in 1940 and World War II undid all achievements of Livonians, with their central organisation and community house ceased their activities.

Culture

Until the 18th century there is only sporadic information about the Livonian written word. The first text in Livonian “The Lord’s Prayer” was published in 1789. Academic research of Livonians and the Livonian language began in 1846 when the first research expedition to Livonians under the leadership of Andreas Johan Sjögren (1794-1855) took place. The first Livonian language dictionary and grammar was published in 1861 (this work was finalized by F. J. Wiedemann), and first Livonian-language books were published in 1863 in London.

This period can be considered as the beginning of the formation of ethnic Livonian intelligentsia. Among the best-known Livonian intellectuals from this time were Jāņ Prints Sr. (1796–1868) and Jāņ Prints Jr. (1821–1904) – poets, compilers of dictionaries and translators of Gospels.

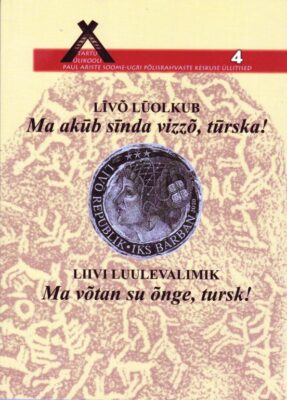

Most Livonian-language books, altogether approximately 20 titles, were published in the 1920s and the 1930s in Estonia and Finland. These were mostly reading books and textbooks. The only work of fiction was Līvõ lōlõd by Karl Stalte, published in 1924 in Tallinn. With the help of Finns, the first Livonian-language magazine Līvli began to be published in 1931.

The arrival of the Soviet rule in 1940 terminated Livonians’ civic and cultural activities, moreover one part of Livonians emigrated. During this period Livonians constituted primarily a research object, to whom academic expeditions were conducted despite multiple challenges. Livonian cultural life began reawakening in the 1970s. In 1972, two Livonian choirs – Līvlist in Riga and Kāndla in Ventspils – were established and soon became main carriers of the Livonian culture in Latvia.

Modern Times

National reawakening of Livonians began in 1988. Activities of the Livonian Union – Līvõd Īt – were restored and Livonian-language literature was being published. The Livonian language was taught in Riga and Ventspils. Since 1989 on the first weekend of August, the Livonian holiday is celebrated in Irē on the Livonian Coast.

In 1991, Livonians were for the first time in history proclaimed an indigenous people of Latvia. Between 1991 and 2004, a Livonian administrative unit Līvõd Rānda was operating as a result of the cooperation between the Republic of Latvia and the Livonian Union. Between 2004-2009, a Livonian department existed within the Latvian Integration Ministry.

Currently there are centres of the Livonian language, culture and history in Kūolka and Staicele. Since 1992, Livonian children’s summer camps have been held in Īre and a Latvian-language newspaper Līvli has been published. The Livonian Culture Centre, established in 1994, has published a Livonian-language magazine Õvā. Several books presenting the Livonian language and culture have been published, most significantly the Livonian poetry anthology Ma akūb sīnda vizzõ, tūrska (1998), Livonian yearbooks, textbook and an ABC.

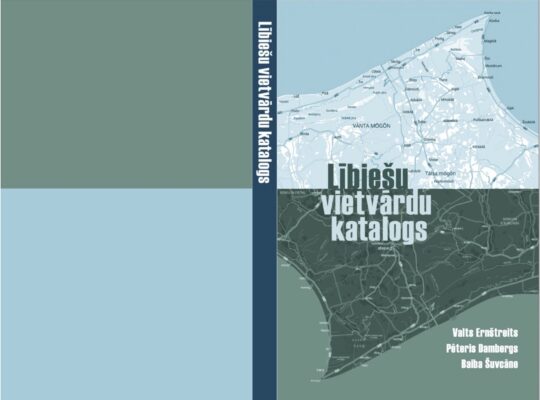

Since 1995, teaching of the Livonian language was for the first time commenced at the Latvian University. In 1999, the Republic of Latvia adopted a support programme of Livonians “Livonians in Latvia” and a language law. According to the this law, the Livonian language has the status of an indigenous language of Latvia. The Republic of Latvia protects and develops the Livonian language and Livonian-language place names can be used on the Livonian Coast.

More recently, the contribution of Livonians to the Latvian society, academic and cultural life has increased. Ilmars Geige and Dainis Stalts have been Livonians’ representatives in the Latvian national parliament, Renāte Blumberga and Valt Ernštreit have defended doctoral dissertations. Livonian folklore groups as well as performers of more contemporary Livonian music – Tulli Lūm and Tai-Tai – have gained recognition. Activists of the Livonian movement proclaimes 2011 as the year of Livonian language and culture.

Symbols

Colours of the Livonian national flag are green, white and blue, symbolising the coast, as it is seen by the fisherman from a boat: the green forest, white sand and blue sea. The Livonian national anthem has an identical melody to the Estonian and Finnish anthems, while the lyrics were written by Kōrli Stalte.

Livonian national days include the Livonians’ day on the first Saturday of August, and the Livonian Flag Day on November 18 (the Livonian green-white-blue flag was consecrated in the Irē church on November 18, 1923).

Further References

- Livones.net – the Livonian Culture, Language and History Portal (in Livonian, Latvian and English)

Virtual Livonia – Introduction to the Livonian language people, their history, and homeland

Online community “Līvõ kēļ” (Livonian Language) on Facebook