Finno-Ugric studies

Finno-Ugric studies or Finnougristics as a scientific field has developed into an exact science during the past 250 years. Pioneers in this field were János Sajnovics and Sámuel Gyarmathy. Great collectors of language material were Antal Reguly and Mattias Aleksanteri Castrén. Finno-Ugric studies reached scientific exactness thanks to the work of Ferdinand Johann Wiedemann, Emil Nestor Setälä, Jószef Budenz and Jószef Szinnyei. A goal of the classical Finnougristics that they created was the historical-comparative study of Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic languages (together known as the Uralic languages), with the goal of reconstructing the proto-language.

History of Finno-Ugric studies

During the past half a century, the concept of classical Finnougristics has broadened: thanks to the tradition started by Kustaa Vilkuna, Gyula Ortutay and Paul Ariste in 1960s of international congresses of Finno-Ugric studies, the concept of Finnougristics has expanded to mean studying all fields of the spiritual and material cultures of the Uralic peoples. Indeed, nowadays the term ‘Finno-Ugric studies’ means the scientific field, which studies the languages, cultures and history of the Uralic peoples.

It might be important for Estonians and language enthusiasts to know that studying small languages can also provide universal knowledge about languages around the world. The recognition of the relationship between Uralic languages has also given rise to ethnology and folklore studies concerning Uralic peoples, as well as the tradition of the kindred people movement as cultural interaction, which is important for Fenno-Ugria.

Finnougristics was one of the earliest fields to apply the comparative-historical method to determine the relationship between languages. Studies of Uralic language contacts have provided valuable information about language change, and this field of research has also contributed to studies of language vitality and preservation, as well as language revitalisation.

International Finnougristics

The International Congresses for Finno-Ugric Studies, held every five years, are the most important forums for cooperation among Finno-Ugric scholars. The 1970 congress in Tallinn was particularly significant for Estonians, as it was the first major international event in the humanities during the Soviet era. Estonians also organised the congress in Tartu in 2000. The most recent congress took place in Tartu (Estonia) in 2025. The next one will be held in Budapest (Hungary) in 2030.

In Estonia, several research and academic institutions are involved in Finno-Ugric studies. These include the Institute of Estonian Language, Estonian National Museum, Estonian Literary Museum, University of Tartu and Estonian Academy of Arts.

In addition to Estonia, Finland (Helsinki, Turku, Oulu, and other universities), Hungary (Budapest, Debrecen, Pécs universities), and Russia, Finno-Ugric studies are also conducted in several other countries, such as Germany (Munich, Hamburg, and Göttingen universities), Austria (University of Vienna), Latvia (University of Riga), Sweden (University of Uppsala), Poland, Norway, Japan, France, and Italy.

Famous Finnougrists

Read more about linguist Tõnu Seilenthal’s selection of scholars who have made pioneering contributions to the development of Finno-Ugric studies.

János Sajnovics (12 May 1733, Tordas – 4 May 1785, Buda)

Sámuel Gyarmathi (15 July 1751, Kolozsvár – 4 March 1830, Kolozsvár)

János Sajnovics was a Hungarian Jesuit who practised astronomy, mathematics and linguistics.

In 1769, as part of an expedition organised by King Christian VII of Denmark and Norway and led by Maximilian Hell, Director of the Vienna Observatory, he travelled to northern Norway to observe the transit of Venus. Hell asked Sajnovics to collect observations on the relationship between the Saami and Hungarian languages.

We can celebrate the birthday of Finnougristics on 10 April, because on this day in 1770, Sajnovics’s work Demonstratio. Idioma ungarorum et lapponum idem esse (“Proof. Hungarian and Lappish are similar”). In the same year, a second, significantly expanded edition of the work was published in Tyrnavia (now Trnava), which also included the oldest Hungarian (and also Finno-Ugric) text Halotti beszéd és könyörgés.

In 1799, the work Affinitas lingvae Hvngaricae cvm lingvis Fennicae originis grammatice demonstrata. Nec non vocabvlaria dialectorvm Tataricarvm et Slavicarvm cvm Hvngarica comparata (“The affinity of the Hungarian language with the languages of Finno-Ugric origin grammatically demonstrated. In addition, the vocabulary of Tatar and Slavic dialects compared with Hungarian”) by Sámuel Gyarmathi, a Transylvanian physician and linguist, was published in Göttingen, which extends the comparison to several Finno-Ugric languages, with emphasis on grammatical comparisons.

These two books, thanks to their well-reasoned arguments and convincing conclusions, have proved to be the first milestones of Fennougistics as a science, as well as the foundations of historical-comparative linguistics before Sir William Jones’s third anniversary lecture in Calcutta in 1786. Sajnovics had already put forward an important idea in his Demonstratio: languages change, they diverge and develop in different directions, and they can become something completely different from each other.

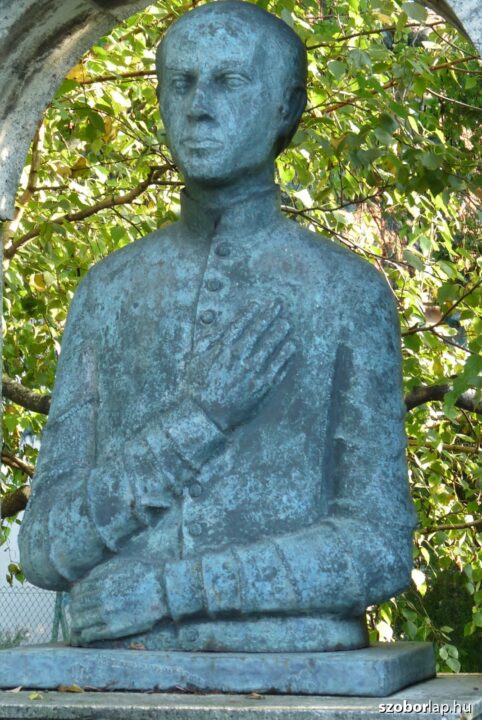

Antal Reguly (11 July 1819, Zirc – 23 August 1858, Buda) was a Hungarian linguist.

Reguly studied law at the Royal University of Pest, graduating in 1839. He was then given the opportunity to study abroad for five months. In Hamburg, Reguly heard about the beautiful nature of the Nordic countries and decided to visit Scandinavia himself. In Stockholm, he met Adolf Ivar Arwidsson from Finland, with whom he discussed the supposed relationship between Finnish and Hungarian. Reguly was inspired by the topic and decided to devote himself to researching the roots of his mother tongue. Reguly gave up his career as a lawyer and travelled to Finland to learn the language and get to know the culture. He became the first Hungarian member of the Finnish Literature Society.

From 1840 to 1841 he lived in Finland, where he studied Finnish and Saami under the guidance of M. A. Castrén. In 1841, he also acquired Estonian, making him the first known Hungarian speaker of Estonian. From 1841 to 1843, Reguly lived in St. Petersburg, preparing for the great expedition to Siberia, and his most important supporter was the Estonian-born St. Petersburg academic Karl Ernst von Baer.

On December 4 1843, Reguly crossed the Ural Mountains, and in the settlement of Vsevolodo-Blagodatskoye he began the most important stage of his life’s work: the study of Mansi and Khanty languages, folklore, religion, ethnography and physical anthropology, as well as the mapping of the Ural Mountains. Thanks to his thorough preparation and excellent linguistic sense, he was soon able to speak Mansi. Reguly’s linguistic guides were the elderly Mansi men Jurkina and Bahtyiár, the latter of whom remained with the scholar until the end of his stay in Manx. In the autumn of 1844, Reguly moved on to the Khanty.

In the spring of 1845, at Baer’s request, he set off back from Beryozovo towards Kazan.

Reguly returned to Hungary in 1847. He took a job as a librarian at the University of Budapest. However, long journeys, primitive living conditions and illness had ruined Reguly’s health. He died in August 1858 at the age of 39, unable to work through and publish the material he had collected. Reguly’s collection of folklore contains a wealth of Mansi and Handi Bear Feast and hero songs and tales, thanks to his excellent informants. He did not write translations or notes alongside the long texts, but memorised it all. His life’s work was far more extensive than expected, taking over a century and several generations of scholars to work through and publish. His manuscript collections were deciphered by Pál Hunfalvy and Bernát Munkácsi, while his manuscript collections were deciphered by József Pápay, Miklós Zsirai and Dávid Fuchs.

Matthias Alexander Castrén (Matias Aleksanteri Castrén, 2 December 1813, Tervola – 7 May 1852, Helsinki) was the first professor of Finnish at the University of Helsinki and a pioneer in the study of Uralic languages and ethnography.

Castrén’s studies laid the foundations for Finnougristics and ethnolinguistics. He wrote the grammars of 14 Siberian languages in all, the first grammars of several of them, and some of them unknown until then.

Having spent his childhood in Lapland and Oulu, Castrén began his studies at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki in 1828, where he became involved in the Lauantaiseura (“Saturday Society”), the flagship of Finnishness and national romanticism. His friends included Elias Lönnrot, Zacharias Topelius, J. L. Runeberg and J. V. Snellman. In 1836, he became a Master of Philosophy, having studied oriental and classical languages and philosophy.

Castrén made his first research trip to Lapland in 1838, after which he published a dissertation based on the Saami folklore and mythology he had collected on the common features of Finnish, Estonian and Saami translations, De affinitate declinationum in lingua Fennica, Esthonica et Lapponica. In 1839, he moved to the Karelian Song Lands, where he met the famous folk singers Arhippa Perttunen and Vaassila Kieleväinen. In 1840, Castrén became lecturer in Finnish and ancient northern languages at the Imperial Alexander University in Helsinki. In 1841, he published a Swedish translation of Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala, the first complete translation of the work into a foreign language.

Castrén’s expeditions from 1841 to 1849 took him from Lapland, through the Arctic coast to Siberia, across the Baikal to China. From his travels, Castrén constantly sent his linguistic notes and archaeological-ethnological collections to St. Petersburg.

He studied the Nenets language and wrote a grammar of the Komi language: Elementa grammatices Syrjaenae, one chapter of which, De nominum declinatione in lingua Syrjaena, was also accepted as a dissertation; he also compiled the grammar of the Mari language, Elementa grammatices Tscheremissae; he studied the Khanty spoken along the Irtysh and Ob Rivers and the forest Nenets who spoke a language hitherto unknown to science; he began a manuscript of the grammar of the Khanty language; and he studied the Selkup, Ket, Kamas, Evenki languages and two Turkic language: Khakas and Tofa.

It was not until 1849 that Castrén, who had suffered from tuberculosis, dysentery and scurvy, reached St. Petersburg and then Helsinki.

In Finland, Castrén’s health improved. The Khanty grammar Versuch einer ostjakischen Sprachlehre nebst kurzem Wörterverzeichnis (1849) was the first to be completed. In Helsinki, Castrén gave his famous lecture, “Hvar låg det Finska folkets vagga?” (“Where was the cradle of the Finnish people?”), according to which the original home of the Finno-Ugric peoples was in the Sayan Mountains on the western slopes of the Altai.

In his doctoral thesis De affixis personalibus linguarum Altaicarum, he compared the personal suffixes of the Uralic, Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic languages. On 14 March 1851, Castrén was appointed the first professor of Finnish language and literature at the University of Helsinki. He lectured on ethnology, Finnish and Finno-Ugric mythology and the Kalevala, but not on linguistics. Tuberculosis prevented him from completing his main work, the grammar of the Samoyed languages: he died at the age of 39.

His extensive and invaluable legacy was edited and published in 1853–1862 by Franz Anton von Schiefner, a St. Petersburg academic from Tallinn. The St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences published twelve volumes of Nordische Reisen und Forschungen von Dr. M. Alexander Castrén in German (reprint Leipzig, 1969).

The M. A. Castrén Society in Finland, which promotes links and cooperation between Finns and other Finno-Ugric peoples, takes its name from Castrén. The Society holds its annual meeting on the anniversary of Castrén’s birth on 2 December each year.

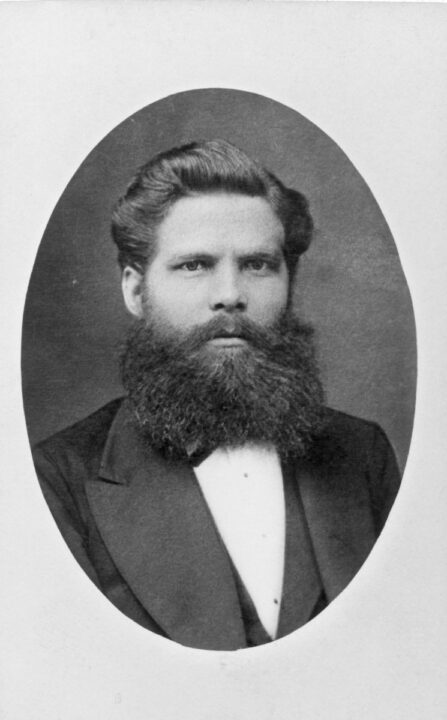

Jószef Budenz (13 June 1836, Rasdorf – 15 April 1892, Budapest) was a German-born Hungarian linguist and one of the most outstanding researchers of his time, who definitively proved that Hungarian is a Finno-Ugric language. He has been called the founder of Hungarian Fennougristics by the academic Péter Hajdú.

Budenz started university in Marburg in 1855 and continued in Göttingen a year later. He studied Indo-European studies and began to work in the field of Altaic studies. He obtained his doctorate in Göttingen in 1858 and, encouraged by fellow Hungarian students, began to study Hungarian. At this time, Wilhelm Schott and Anton Boller published studies comparing Hungarian with Ugric as well as with Turkic and Mongolian. Inspired by these, Budenz began to study Turkish, with the aim of devoting himself to a thorough study of the Ural-Altaic language family. Pál Hunfalvy invited Budenz to Hungary. In May 1858, at the age of twenty-two, Budenz arrived in Pest. His ability to master languages is perhaps demonstrated by the fact that he wrote a few articles in Hungarian as early as the autumn of the same year.

At first, he compared Hungarian to Turkish, convinced that it was more closely related. However, his research led him to a negative conclusion, as he became convinced that the Hungarian-Turkish comparisons were largely based on borrowings, and that in fact the Finno-Ugric basic vocabulary, with its regular phonetic correspondences and similar grammatical structure, pointed to the Finno-Ugric character of the Hungarian language. In 1869, Budenz’s friend Ármin Vámbéry published a comprehensive work on Hungarian-Turkish-Tatar word comparisons that was severely criticised by Budenz. The “(Finno-)Ugric-Turkish war” broke out, which went beyond the bounds of scholarship and has remained a vexed issue in Hungarian society. Budenz emerged victorious, although he lost a friend.

In 1872, the world’s first Department of Finno-Ugric Studies was founded at the University of Pest (then called the Department of Comparative Altaic Linguistics). It was headed by József Budenz for twenty years until his death. During this period, Budenz’s most notable works were the Hungarian etymological dictionary Magyar-ugor összehasonlító szótár (“Hungarian-(Finno-)Ugric Comparative Dictionary”, 1873–1881) and Az ugor nyelvek összehasonlító alaktana (“Comparative Morphology of the (Finno-)Ugric Languages”, 1884–1894), which were published on the basis of a manuscript by his student Zsigmond Simonyi.

On 15 April 1892, József Budenz suffered a heart attack, of which he died. He is buried in the Kerepesi Cemetery of Budapest, the final resting place of Hungary’s great figures.

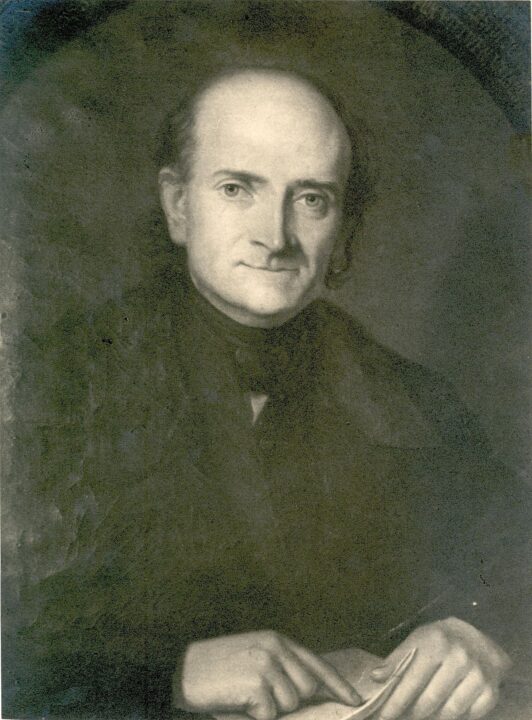

Ferdinand Johann Wiedemann (30 March 1805, Haapsalu – 29 December 1887, St. Petersburg) was a linguist, researcher of Estonian and other Finno-Ugric languages.

Wiedemann was a polyglot who, according to his university colleague, the Armenian writer Hatsatur Abovyan, knew more than twenty languages. His family was German-speaking, but as a child he studied French and Russian at home, alongside German and Estonian, and at the Tallinn Provincial Gymnasium (now Gustav Adolf Grammar School) he also studied classical languages.

After his university studies at the University of Tartu (1824–1826), he worked as a teacher of ancient languages in Mitau (Jelgava) and later for twenty years as the head teacher of Greek at his alma mater, the Tallinn Governorate Gymnasium. He became interested in the Finno-Ugric languages of Russia, which were still little known at the time, and collected language knowledge from soldiers serving in the Tallinn garrison. He was interested not in the history of languages, but in the structure of languages and the typology of languages developed by Wilhelm von Humboldt. Wiedemann wrote descriptive grammars of the languages of Erzya, Komi, Hill Mari and Udmurt: Versuch einer Grammatik der syrjänischen Sprache : nach dem in der Übersetzung des Evangelium Matthäi gebrauchten Dialekte (1847), Versuch einer Grammatik der cheremissischen Sprache : nach dem in der Evangelienübersetzung von 1821 gebrauchten Dialekte (1847), Grammatik der Wotjakischen Sprache nebst einem kleinen wotjakisch-deutschen und deutsch-wotjakischen Wörterbuche (1851), Grammatik der ersa-mordwinischen Sprache : nebst einem kleinen mordwinisch-deutschen und deutsch-mordwinischen Wörterbuch (1865).

For his outstanding linguistic work, the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences elected him correspondent member in 1854 and academician in 1857. Wiedemann therefore had to move to St. Petersburg. As an academic, he also started linguistic research trips: he collected additional material to Sjögren’s Livonian heritage in Livonia and published Joh. Andreas Sjögren’s gesammelte Schriften, Volume 2, Theil 1, Livische Grammatik nebst Sprachproben (1861). He took a greater interest in the languages of the Permic world, especially the Komi language, with his Syrjänisch-deutsches Wörterbuch nebst einem Wotjakisch-deutschen im Anhange und einem deutschen Register (1880) and Grammatik der syrjänischen Sprache : mit Berücksichtigung ihrer Dialekte und des Votjakischen (1884).

Mihkel Veske (28 January 1843, Holstre – 16 May 1890, Kazan) was an Estonian theologian, poet and linguist, the first Estonian doctor of linguistics.

Veske’s studies abroad began at the Leipzig Mission, but theological debates failed to captivate the young man, who decided to dedicate his life to serving his nation, its language and the revival of its people. In 1867, he entered the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Leipzig, where he initially studied Indo-European Studies. The University of Leipzig was the birthplace of the Neogrammarian school. The Neogrammarian hypothesis was based on the idea that language changes occur according to certain laws – for example, that sound changes are not random but regular. They developed a more rigorously systematic method for comparing and reconstructing languages, especially Indo-European languages. Veske decided to apply this method to Finno-Ugric languages: in 1872 he defended his doctoral thesis Untersuchungen zur vergleichenden Grammatik des finnischen Sprachstammes (“Studies on the Comparative Grammar of Finnic Languages”). He then worked as a lecturer of Estonian language at the University of Tartu from 1874–1887 and tried to open a chair of Estonian language at the University of Tartu. Veske could have become the first professor of Estonian language at the University of Tartu, but his excessive nationalism probably doomed him during the Russian era. In 1885, he was sent on a research trip to Hungary, where he was perhaps the first Estonian to master the Hungarian language with great speed. He was also the first to translate Sándor Petőfi’s poems from Hungarian. From Hungary, Veske moved to Kazan, where he worked as a lecturer of Finno-Ugric languages at the university from 1886 until his death. Veske also made two expeditions to the Finno-Ugric peoples in Kazan and collected nearly 200 Mari and Mordvin songs. In 1889, Veske published an important study on the dialectal classification of the Mari language, “Studies on the dialects of the Cheremis language”. He has brought the tree name nulg to Estonian from Mari. Veske’s most voluminous study is the first volume of “Slavic-Finnic Cultural Relations according to the Data of Language” published in Kazan in 1890, in which he attempted to explain the Slavic and Finno-Ugric borrowings between the languages. He showed convincingly that the whole of northern Russia had been inhabited by Finno-Ugric tribes, as evidenced in particular by numerous hydronyms.

Among other things, Veske was the first to go down in the history of the study of the Estonian language, when in his work “The good doctrine of the Estonian language and the way of writing” (1879) he theorised that the Estonian language has three lengths for vowels and consonants – short, long and overlong.

Veske was one of the leaders of the nationalist movement of the Estonian Age of Awakening, advocating the views of Carl Robert Jakobson, and from 1882 to 1886 he was president of the Estonian Society of Writers. In 1874, Veske published a collection of poetry entitled “Songs with Melodies”. In 1880, Veske and Peter Abel published the choral songbook “Song Collection…”, which contained 13 songs by Veske. Veske’s patriotic poems “Do you know the land…” and “Let’s Go Up the Mountains” have found a place in the popular song repertoire and the soul of the people.

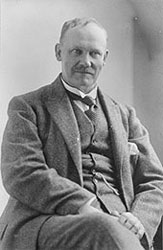

József Szinnyei (26 May 1857, Pozsony – 14 April 1943, Budapest) was a Hungarian linguist, Academician of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Dean of the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Budapest.

Szinnyei studied Hungarian and German literature and Finno-Ugric Linguistics at the University of Budapest. However, as a student of József Budenz, he was already then most interested in Fennougristics. After graduating in 1879, he was awarded a one-year national scholarship for linguistic studies in Finland. While there, he collected material for a future Finnish-Hungarian dictionary and, together with Antti Jalava, wrote a Hungarian grammar in Finnish (Unkarin kielen oppikirja). From Finland he also took his wife, Hilma Rosendahl, an actress of the Finnish National Theatre, with him.

In 1881, he worked at the National Museum. In 1883, Szinnyei was appointed private lecturer in Finnish language and literature at the Budapest University of Science, and the following year he was elected a corresponding member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. From 1886 to 1893, Szinnyei worked as a professor of Hungarian language and literature at the Franz Joseph University of Science in Kolozsvár, which was recently founded in 1872, while also lecturing on Finno-Ugric subjects. In 1893, he was appointed professor of Ural-Altaic comparative linguistics at the Budapest University of Science, continuing his work at the Academy of Sciences, where he was elected a full member of the Academy in 1896, and 10 years later also Secretary of the Department of Language and Fine Arts. From 1923 to 1924 Szinnyei was also Rector of the Budapest University of Science.

József Szinnyei was also the author of the first university textbooks on Finno-Ugric linguistics: Magyar Nyelvhasonlítás (“Hungarian Language Comparison”, 1896), which was published in seven revised editions until 1927, and based on this, the German textbook Finnisch-ugrische Sprachwissenschaft (1910, 2nd edition “Zweite, verbesserte Auflage”, Berlin, W. de Gruyter, 1922).

It should not be overlooked that Hungarian schoolchildren learned to read and know the grammar of their mother tongue according to Szinnyei’s school textbooks: his Hungarian reading books for grades I–III were published in 11 editions between 1887 and 1908, his systematic Hungarian grammar in 11 editions between 1888 and 1907, and his Hungarian grammar based on syntax in as many as 14 editions between 1884 and 1908.

Emil Nestor Setälä (27 February 1864, Kokemäki – 8 February 1935, Helsinki) was a Finnish linguist, folklorist and politician, professor of Finnish language and literature at the University of Helsinki 1893-1929, Chancellor of the University of Turku 1926–1935, and from 1930 director of Suomen suku, a research institute he founded.

Setälä became the man who defined the agenda and approach of Finnish linguistics for decades. Setälä’s most enduring scholarly contribution is the provision of a relatively reliable picture of Finno-Ugric consonantal phonetic relationships in Finnic and other Finno-Ugric languages. Setälä also served in five Finnish governments as Minister of Education and influenced the creation of several Young Republic Acts, serving for three months as Acting Prime Minister (the so-called Setälän tynkäsenaatti – “Setälä’s Rump Senate”) in 1917. Next, as a member of the Svinhufvud Senate, Setälä wrote the text of the Finnish independence manifesto.

At the age of only 16, Setälä, as a student at the Hämeenlinna Lyceum, published Suomen kielen lauseoppi (1880), a Finnish phrase book, which was used as a school textbook for decades until the second half of the 1900s, as well as the later Suomen kielen oppikirja (“Finnish language textbook”).

Setälä graduated in 1885 from the University of Helsinki with a Bachelor of Philosophy, with laudatur degrees in Finnish, Latin, Sanskrit and comparative linguistics. His dissertation on the history of the formation of grammatical tenses and moods in the Finno-Ugric languages, Zur Geschichte der Tempus und Modusbildungen in den finnisch-ugrischen Sprache, was completed in 1886. Between 1888 and 1890 Setälä made several research trips to Livonians, Veps and Votes, collecting material for a comparative phonetic history of the Finnic languages.

Both Setälä and his teacher Arvid Genetz applied for the post of professor of Finnish at the University of Helsinki, which became vacant with the death of August Ahlqvist. In 1893, the professorship of Finnish was split into two: Genetz became professor of Finno-Ugric Studies and Setälä professor of Finnish. He was the first to use Finnish instead of Swedish in the university’s Consistory meetings. In 1890–1891, he wrote an extensive, pioneering work on the phonetic transcription of the consonants of the Finnic languages, Yhteissuomalainen äännehistoria I-II. Konsonantit (“Finnic phonology I-II. Consonants”), which became a model for the compilation of phonological histories for the Finnic languages. The extensive plan for the collection and publication of Finnish and Finno-Ugric languages, planned in 1896, has largely been realised: the compilation and publication of a dictionary of Finnish dialects, a dictionary of the old written language, a dictionary of the modern Finnish language, a dictionary of Finnish etymology and a dictionary of Karelian was proposed by Setälä. This plan also served as a model for Estonians.

The most important folkloristic works were Kullervo-Hamlet (1904–11), “Väinämöinen and Joukahainen” (1913) and “The Riddle of Sampo” (1932). In them, he took the view that the characters of “Kalevala” were not real people, because there is no evidence of the lives of Väinämöinen, Ilmarinen, Louhi and others. He solved Sampo’s riddle with the help of the North Star and the World Pillar.

As an old man, Setälä returned to politics: he was Minister of Education in 1925 and Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1925 to 1926. From 1927 to 1930, he was Finland’s ambassador in Copenhagen and Budapest.

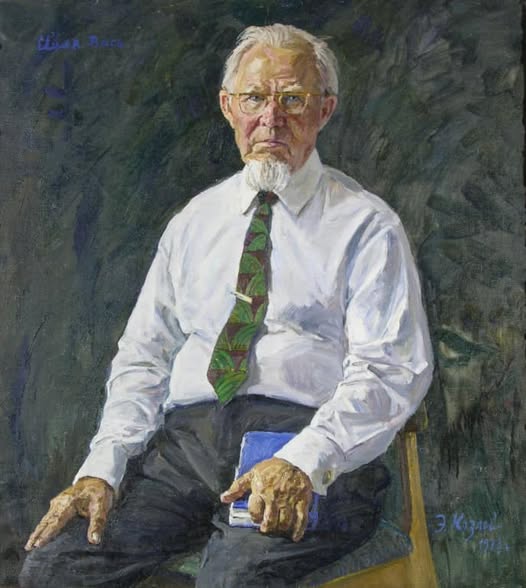

Vasili Lytkin (Василий Ильич Лыткин (Komi: Илля Вась), 27 December 1895, Tentyukovo – 27 August 1981, Moscow) was a Komi linguist and poet.

After participating in the First World War and the Russian Civil War, he graduated from the Moscow University Faculty of Linguistics in 1925 and later completed his postgraduate studies there. As a very young man, he was sent on a two-year scientific mission to Finland, Germany and Hungary. In 1927, he obtained a doctorate in philosophy from the Royal Péter Pázmány University in Budapest. Lytkin was an associate professor at Moscow University from 1930 to 1933, and from 1932 a lecturer at the Komi Pedagogical Institute. In 1933, Vasili Lytkin was arrested in the so-called “SOFIN Affair” in Moscow. In 1933, Vasily Lytkin was arrested during the SOFIN trial and sentenced to nine years’ imprisonment in a prison camp in the Far East.

After five years of imprisonment, he was released without the right to return to his homeland. In 1939, he was appointed head of the Department of Linguistics at the Pedagogical Institute in Chkalov (now Orenburg) and head of the Russian Language Department at the Pedagogical Institute in Ryazan. In 1956 he was fully rehabilitated and allowed to live and work in Moscow. From 1959 until his retirement in 1972, he worked at the Institute of Linguistics of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, where he headed the Finno-Ugric Languages Section from 1962.

Lytkin’s research topics were all based on his mother tongue, the Komi language. The most important was Древнепермский язык и историческая грамматика (“The Old Permic language and historical grammar”), with which he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philology in 1946. It is known that the texts written in the Old Permic script, or Anbur, created in 1372 by the Bishop of Perm, Stephen of Perm, are among the oldest Finno-Ugric texts. The main works of Permistics include “The Ancient Permic Language: Reading of Texts, Grammar, Dictionary” (1952), “Historical Vocalism of Permic Languages” (1964), and “Short Etymological Dictionary of the Komi Language” (1970, with J. Gulyayev).

Vasili Lytkin was a writer beloved by the Komi people in his youth, and his first poem was published in 1918. Under the pen-name Illya Vas’, he wrote poems, verse short stories and children’s poetry. In all, he published 13 collections of poetry, the most important of which is Кывбуръяс (“Poems”, 1929). He translated into Komi the poetry of Sándor Petőfi, Aleksandr Pushkin, Fyodor Tyutchev, Vladimir Mayakovsky and others. Only a small part of his planned translation of Kalevala was completed.

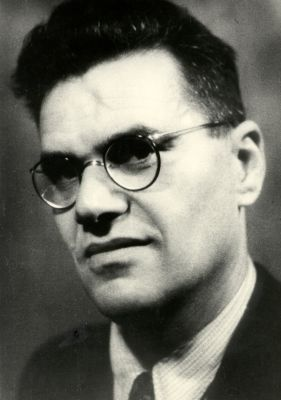

Wolfgang Steinitz (28 February 1905, Breslau – 21 April 1967, (Ost-)Berlin) was a German linguist, folklorist and politician from a family of Jewish intellectuals.

At the University of Berlin he studied Finno-Ugric languages, Finno-Ugric folklore and ethnography. After graduating, he had the opportunity to study further in Finland and Estonia on a scholarship. He described the period from Tartu 1930 to 1931 as the happiest time of his life. He became friends with Paul Ariste, a relationship that lasted until his death. During the Estonian period, W. Steinitz translated Ilmari Manninen’s study of Estonian material culture Die Sachkultur Estlands into German.

After returning to his homeland from Estonia, W. Steinitz began to work at the Hungarian Institute at the University of Berlin. In April 1933, however, he lost his job and in 1934, as a Jew and a convinced communist, had to flee the terror. On his arrival in Finland, he received a recommendation from the Finns to go to work at the Institute of the Northern Peoples in Leningrad, which needed a specialist in Finno-Ugric languages. Steinitz’s doctoral thesis on parallelism in Karelian folklore, Parallelism in Finnisch-Karelischen Volkdichtung: Untersucht an den Liedern des Karelischen Sängers Arhippa Perttunen, had just been published in the prestigious Folklore Fellows Communications series. The years of emigration to Leningrad 1934–1937 gave a lot to W. Steinitz: with the help of his students, the emerging intelligentsia, he delved deeply into the languages of the Khanty and, to some extent, the Mansi, collected from them a wealth of material on the languages, as well as copious amounts of Khanty and Mansi folklore. He also participated in an expedition to Siberia in 1935.

In 1937, W. Steinitz and his family left Leningrad in 1937 to escape the Stalinist terror. The difficult years began, first in Estonia and then in Sweden. In spite of the hardships, W. Steinitz was able to publish a work on Khanty folklore Ostjakische Volksdichtung und Erzählungen (I – Tartu, 1939; II – (Tartu-)Stockholm, 1941), a Khanty-language reader with grammar and dictionary, an overview of the vocalism of the Mansi language and a history of the vocalism of the Finno-Ugric languages Geschichte des finnisch-ugrischen Vokalismus (Stockholm, 1944 and Berlin, 1964). In explaining the oldest Finno-Ugric vocalism, he took as his point of departure the Ob-Ugric languages, which he considered to have best preserved their original state.

After the end of the war, Steinitz returned to his homeland in 1946. He began to actively re-establish scientific life in East Germany. At the Humboldt University in Berlin, he was appointed professor of Finno-Ugric languages. As vice-president of the German Academy of Sciences, he was also for a long time the organiser of scientific work. In addition to the large German dictionary and Russian textbooks, he continued his work on Finno-Ugric languages. His works on the vocalism of the Ob-Ugric languages were Geschichte des ostjakischen Vokalismus (1950) and Geschichte des wogulischen Vokalismus (1955). Of the fifteen volumes of the dialectological and etymological dictionary of the Khanty language, Dialektologisches und etymologisches Wörterbuch der ostjakischen Sprache (1966–1993), only the first two were printed.

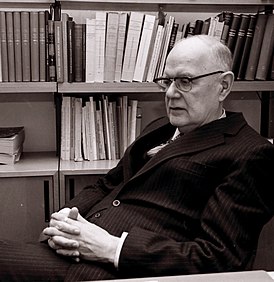

Erkki Itkonen (26 April 1913, Inari – 28 May 1992, Helsinki) was a Finnish academic, one of the most internationally recognised scholars of Finno-Ugric languages, and one of the most notable Finnougrists of the 20th century.

He began his academic career as a researcher of Saami languages, his doctoral thesis in 1939 was on the vocalism of East Saami. Between 1986 and 1991, Itkonen’s work resulted in the publication of the four-volume Inari Saami dictionary, Inarilappisches Wörterbuch: spoken by only a few hundred people in Finland, this 1,548-page dictionary has made Inari Saami one of the best-documented minority languages in the world.

Itkonen was Professor of Finno-Ugric Studies at the University of Helsinki from 1950 to 1963. He was a member of the Academy of Finland from 1964 to 1983. His special research interest was the history of phonology. Modern understanding of the phonetic relationships between Finno-Ugric languages and their development is based mainly on the studies of Itkonen and his students Pekka Sammallahti, Juha Janhunen and others. Itkonen’s work has also resulted in a detailed explanation of the relationships between the Saami languages and the Finnic languages.

Itkonen was the editor-in-chief of the seven-volume, 2,293-page Finnish etymological dictionary Suomen kielen etymologinen sanakirja (1955–1981), and also started editing the next-generation etymological dictionary Suomen sanojen alkuperä (“The Origin of Finnish Words”). For a long time he was the editor of the Sápmelaš (1934–1950) and chairman of the Finno-Ugrian Society (1969–1978).

Paul Ariste (3 February 1905, Rääbise – 2 February 1990, Tallinn) was an Estonian linguist and a Member of the Estonian Academy of Sciences (1954).

From 1925 to 1929 he studied Estonian, Finno-Ugric languages, folklore and Germanistics at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Tartu. Alongside his studies and later, Ariste worked at the Archives Library of the Estonian National Museum (1925–27) and at the Estonian Folklore Archives (1927–31).

Paul Ariste obtained a master’s degree in 1931. In 1931–33 he was a fellow of the University of Tartu at the Universities of Helsinki, Uppsala and Hamburg, and from 1933 he was a lecturer at the University of Tartu. Ariste defended his doctoral dissertation on “Phonology of the Hiiumaa dialect” in 1939. In 1946–77 he was head of the Department of Finno-Ugric Languages at the Technical University of Tartu, professor (1949), and academician of the Estonian Academy of Sciences (1954). It is difficult even to count the number of his honours: Honorary Scientist of the Estonian SSR (1965), Honorary Member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (1966), Foreign Member of the Finnish Academy of Sciences (1969), Honorary Doctor of the University of Helsinki (1969), Honorary Doctor of the University of Szeged (1971), Honorary Doctor of the University of Tampere (1975), Honorary Doctor of the University of Latvia (1989), Foreign Member of the Academy of Finland (1980), etc.

At the University of Tartu, Paul Ariste taught several Finno-Ugric languages, Finnougristics, general linguistics, Finnish, Swedish, Latvian, Low German and Esperanto. His rapport with students was legendary.

Paul Ariste was also an outstanding organiser of research, and the Department of Finno-Ugric Languages at the Tartu State University, which he directed, became a central institution of learning for the Finno-Ugric peoples of the then Soviet Union. In essence, he founded the school of Estonian Finno-Ugric studies, and at his instigation several of our linguists specialised in Finno-Ugric languages. Under Paul Ariste’s encouragement, almost a hundred Finno-Ugric linguists living in the Russian Federation came to the University of Tartu for post-graduate studies and defended their theses for a Bachelor or Doctor of Science. Ariste himself supervised about 60 dissertations and was an opponent in the defence of more than 150 dissertations.

In addition to his work as a university professor, he was the head of the Finno-Ugric Languages Sector of the Institute of Language and Literature of the USSR State Academy of Sciences in 1957–60, and in 1965 Ariste founded the journal Sovetskoe Finno-Ugricovedenie (current Linguistica Uralica), which he edited until his death. Paul Ariste was one of the initiators of the international Finno-Ugric congresses in 1960 and president of the III International Finno-Ugric Congress in Tallinn (1970).

Paul Ariste’s linguistic love was the Votic language, which he first heard from Darja Leht in 1924 at a museum party in Tallinn. In 1942, Ariste took part in an expedition organised by the University of Tartu to the area where the Votes lived. He collected a wealth of material on his main field of research, the Votic language and folk culture. His manuscript records are collected in a “Votic ethnology” binder containing 5,662 pages.

His most important works include “Estonian Swedish loanwords in Estonian” (1933), “Phonology of the Hiiumaa dialect” (1939), “Swedish-Estonian dictionary” (1939, with P. Wieselgren and G. Suits, Uppsala, 1976), “Estonian Phonetics” (1953, 1981–82), “Votic language grammar” (1948, in English, Bloomington, 1968), “Votic folk calendar” (1969), “Ferdinand Johann Wiedemann” (1973), “A Vote from the cradle to the grave” (1974), “Votic folktales” (1977), “Votic riddles” (1979), etc. In total, Paul Ariste wrote more than 1,300 scientific articles.

Paul Ariste’s contribution to Finno-Ugric linguistics and to the development of cooperation between Finno-Ugric peoples is inestimable. His contribution to the development of the national humanistic intelligentsia of the Finno-Ugric peoples is immense. Thanks to Paul Ariste, a positive image of Estonia and Estonians developed among Finno-Ugric peoples living in Russia, a kind of role model. Many of Paul Ariste’s students became leaders of Finno-Ugric national movements in the late 1980s and raised national issues in their own country. Under Paul Ariste’s influence, hundreds of Finno-Ugric students entered Estonian higher education institutions in the 1990s and are now fighting for the survival of their own languages and cultures.